Gastroenterological Malignancies

- related: Hemeonc

- tags: #hemeonc

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in North America, yet it is largely preventable through screening. CRC screening of average-risk patients is discussed in MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine. Most colon cancers are adenocarcinomas that begin in the inner lining and progress to involve or spread beyond the full thickness of the bowel wall, then to regional lymph nodes, and subsequently to distant organ metastases. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, risk factors (and screening high-risk patients), and clinical manifestations will be discussed in MKSAP 18 Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Recent evidence suggests tumors on the right side of the large intestine (cecum, ascending colon, and proximal two thirds of transverse colon) have a completely different biology, likely related to embryologic origin, and a substantially worse prognosis than tumors on the left side (distal one third of transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum). Symptoms may also differ based on tumor location, with left-side tumors more likely to cause a change in bowel habits. Cancer in the cecum, with a larger lumen and less formed stool, does not generally cause a change in bowel habits until the tumor is advanced in size, but may present with iron-deficiency anemia with occult, chronic blood loss. Colon cancer at any location may also present with hematochezia, pain, or acute clinical signs from perforation or obstruction.

Approximately 15% of CRCs lack one or more mismatch repair enzymes and are known as mismatch repair deficient (dMMR)–CRC. This manifests itself as increased microsatellite instability (MSI) in the cancer cell's DNA; the terms dMMR and MSI are essentially synonymous. Most guidelines now recommend that all CRCs should be screened for dMMR or MSI. Approximately 25% of patients with dMMR tumors will have Lynch syndrome, which is associated with a high lifetime risk of CRC as well as endometrial and other cancers. Patients and family members with Lynch syndrome require formal genetic counseling and more intense cancer surveillance. Mismatch repair status or the tumor can affect treatment choices in patients with stage II or stage IV cancer as discussed below.

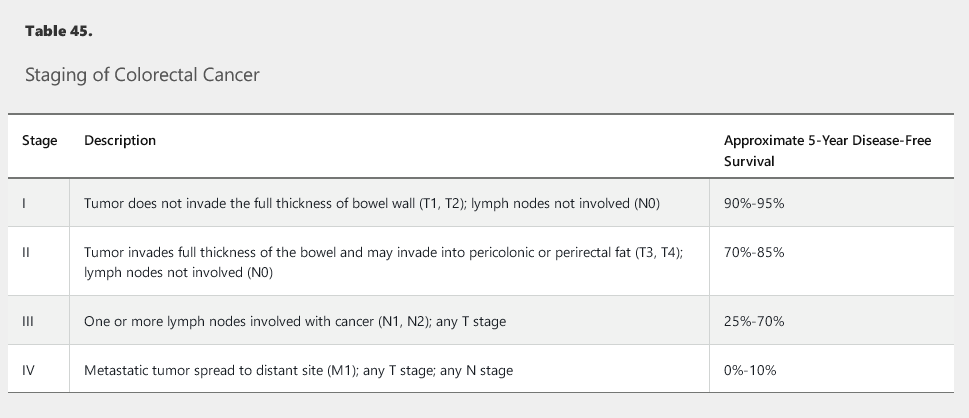

Staging

Staging with the TNM cancer staging system is the first step in treatment planning (Table 45). Evaluation includes serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) in addition to routine laboratory studies; a full colonoscopy (if possible); and contrast-enhanced CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. Rectal cancers also require a rectal MRI or endorectal ultrasonography, both of which offer more precision in assessing tumor penetration and lymph node involvement. PET scans have not been demonstrated to provide greater accuracy in staging and should not be routinely used for preoperative staging or postoperative surveillance.

Treatment

There are important differences in the treatment of rectal versus colon cancer. Sphincter preservation is an important consideration as it obviates the need for a permanent colostomy. Due to its pelvic location, local failure in rectal cancer is associated with higher morbidity and worse outcome. Neoadjuvant therapy causes significant down-staging of the primary tumor before resection and is associated with higher rates of sphincter preservation and local control.

Rectal Cancer

Rectal cancers without full thickness penetration of the bowel wall or enlarged lymph nodes are stage I and are treated with surgical resection. Small tumors may be resected by a transanal approach, decreasing postoperative morbidity. Unless more extensive disease is found at operation, no further treatment is warranted.

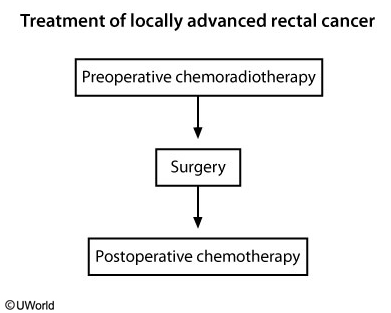

Full-thickness tumors (stage II) and involved lymph nodes or invading into muscularis propria (stage III) require radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. The optimal sequencing and combining of the three treatment modalities is being studied. Attempts are made to preserve anal sphincter function, but distal rectal lesions may require an abdominal-perineal resection and permanent colostomy.

The standard of care for patients with T3/T4 tumor, with or without regional lymph node involvement, is preoperative chemoradiotherapy followed by curative surgical resection, followed by further chemotherapy. Chemotherapy during radiation therapy (to radiosensitize the tissue), followed by surgery and postoperative chemotherapy, is associated with improved cure rates in these patients.

The flow chart shows the sequence of treatment in locally advanced (T3/T4) rectal cancer.

Intravenous 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or oral capecitabine, a prodrug that is converted into 5-FU, is given concurrently with radiation therapy. The chemotherapy may be associated with edema and erythema of the palms and soles that may progress to blistering and necrosis (hand-foot syndrome), mucositis, diarrhea, and neutropenia. Leucovorin, 5-FU, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) or capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CAPOX) regimens are typically used for the chemotherapy-only portion of the treatment. Oxaliplatin often causes a peripheral neuropathy that does not resolve fully in some patients.

Following therapy, patients with rectal cancer should be evaluated at approximately 6-month intervals for up to 5 years with a history, physical examination, and serum CEA level assessment. Contrast-enhanced CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are typically obtained annually for 5 years.

Colon Cancer

Nonmetastatic colon cancers are managed with initial surgery. Pathologic evaluation determines further treatment.

Patients with stage II cancer lacking high-risk features, such as poorly differentiated histology, T4 primary tumor, lymphovascular invasion, inadequate lymph node sampling, elevated postoperative CEA, or perforation or obstruction, are unlikely to benefit from adjuvant treatment. Patients with one or more of these risk factors may be considered for adjuvant 5-FU or capecitabine. All stage II colon tumors should be assessed for MSI or dMMR, because such tumors, when stage II, are at low risk for recurrence, do not benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy, and should not be treated regardless of the presence of other potential risk factors.

FOLFOX and CAPOX, given for approximately 6 months, are equally acceptable adjuvant chemotherapy regimens and reduce the risk of cancer recurrence and death in patients with stage III cancer.

As with rectal cancer, routine evaluation and serum CEA assessment should be done at approximately 6-month intervals, with annual CT scans for up to 5 years after therapy.

Postoperative surveillance following curative resection is used to identify oligometastatic disease in the liver or lung that may be resectable. Patients with metastatic foci confined to liver or lung should be referred for surgical evaluation. Complete resection of metastatic foci may lead to cure in 25% of these patients. Contrast-enhanced CT scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are recommended annually for up to 5 years postoperatively. PET scanning should not be used for routine surveillance. Colonoscopy is recommended one year after resection (or 3 to 6 months after resection if a complete colonoscopy was not done preoperatively), and then in 3 years, followed by every 5 years, unless abnormalities are found. In 2016, the United States Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer recommended that flexible sigmoidoscopy or endoscopic ultrasound be performed every 3 to 6 months for the first 2 to 3 years after surgery in patients with rectal cancer who are at increased risk for local recurrence.

Metastatic Disease

All metastatic CRC requires molecular analysis for KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF gene mutation status as well as dMMR determination. This rarely affects the choice of first-line therapy but will define subsequent treatment options, discussed later. These tests can be done on either the primary tumor or a metastasis; rebiopsy of metastases for the purpose of these studies is rarely needed.

Patients with metastatic disease limited to the liver should be evaluated for surgical resection with curative intent. Unresectable metastatic CRC is treatable but not curable. Although chemotherapy may be palliative and even extend survival, patients who have a poor performance status may not benefit or may have unacceptable toxicity. A careful discussion should be undertaken with the patient to establish goals of care and expectations.

5-FU is at the center of most treatment regimens, with longer infusions preferable to bolus administration. Newer drugs have failed to replace 5-FU, but leucovorin is often combined with 5-FU, or capecitabine can be an alternative to 5-FU. Other cytotoxic agents used in metastatic CRC include irinotecan and oxaliplatin. The anti–vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) monoclonal antibody bevacizumab is often given concurrently with first-line cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens. This agent has essentially no antitumor activity in CRC on its own, but it does potentiate other chemotherapies, resulting in a modestly increased duration of progression-free survival, and in some studies, in increased duration of overall survival. Studies have shown that continuing an anti-VEGF agent with second-line chemotherapy also modestly improves overall survival. Bevacizumab commonly causes hypertension, sometimes requiring antihypertensive medication. It also interferes with wound healing and needs to be discontinued 6 to 8 weeks before elective surgery and withheld for at least a month after surgery. Very rare but potentially life-threatening side effects include arterial thrombotic events such as myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accidents, and gastrointestinal perforations.

Panitumumab and cetuximab are monoclonal antibodies that bind to and block activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). They are potentially active only in tumors that are nonmutated (wild-type) KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF genes. In addition, more recent data suggest that these agents may only have activity in tumors derived from the left side of the large intestine. The major side effect of these agents is an acneiform rash, which can be painful, pruritic, and socially debilitating. There is a tight correlation between rash and antitumor activity, and patients who have only a mild skin rash are unlikely to benefit from these agents. Anti-EGFR agents should not be used concurrently with anti-VEGF agents; two large randomized trials found an unexpected detriment with concurrent use.

Thus far, immune checkpoint inhibitors have been inactive in metastatic CRC, with the exception of those rare tumors that are metastatic and dMMR. The programmed death 1 (PD-1) receptor inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab have both shown activity in such patients; however, dMMR tumors make up only 1% or 2% of metastatic CRC.

Multigene sequencing may open some experimental options, but it does not yield actionable information in terms of standard management options at this time. Thus the expense is not warranted outside of a potential research setting.

Anal Cancer

Anal cancer is a human papillomavirus (HPV)–associated malignancy. Unlike rectal cancer, which is an adenocarcinoma, anal cancer is a squamous cell carcinoma. Anal cancer is often curable with combined radiation and chemotherapy; surgery is typically not indicated. Mitomycin plus 5-FU or capecitabine is the standard chemotherapy regimen. Although complete regression may be observed as soon as 8 weeks after radiation, responding tumors may continue to regress for up to 6 months after radiation. If tumor growth is seen after radiation, then salvage surgery with a permanent colostomy is indicated. Distant metastases are rare. When they do develop, chemotherapy with oxaliplatin, cisplatin, or carboplatin is often active.

Although HPV vaccination would be expected to be as effective at cancer prevention as it is with other HPV-related malignancies, there is no evidence that HPV vaccination plays a role in treatment or post-treatment management of patients with anal cancer. See MKSAP 18 General Internal Medicine for further discussion of HPV vaccination.

Pancreatic Cancer

There are approximately 53,000 patients diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic cancer per year in the United States. Mortality is high, with 42,000 deaths expected annually. Only patients who can undergo a complete resection have a chance of cure. When disease is unresectable because of invasion into critical vascular structures, median survival is approximately 1 year. For those with metastatic disease, median survival is typically less than half that.

Most pancreatic cancers lack a genetic predisposition, although 5% to 10% of patients have either a strong family history of pancreatic cancer, an identifiable mutation that confers increased risk, or both. Genetic counseling and germline testing is recommended for all individuals diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic cancer as such information may impact therapeutic decisions and benefit family members. Chronic pancreatitis, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, high red meat consumption, alcohol abuse, and tobacco use are implicated risk factors.

Painless jaundice, abdominal pain, weight loss, persistent fevers, or protracted nausea and vomiting may be presenting symptoms. Manifestations of hypercoagulability, including Trousseau syndrome (a migratory superficial thrombophlebitis of the lower extremities), chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation, deep venous thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism, may be the initial manifestations of underlying pancreatic cancer.

A contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and abdomen (or noncontrast chest CT and abdominal MRI) are appropriate for staging and treatment planning. PET scans have not been shown to add value in pancreatic cancer and are not part of standard management. For patients whose disease is confined to the pancreas with or without involved local regional lymph nodes, resectability is the most important question. Endoscopic ultrasonography may help in staging and is used to more precisely guide diagnostic needle biopsy. Some patients with clinical features that strongly suggest malignancy may not require such preoperative biopsy, as false-negative results would not obviate the need for surgical resection. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography may also be useful in delineating resectability in borderline patients. Conversion therapy—using radiation or chemotherapy to convert locally unresectable disease to resectable—has garnered interest, but evidence defining how successful this approach actually is remains limited and preliminary.

Patients without evidence of metastatic disease who appear to have technically resectable disease should undergo resection.

Patients who are medically well enough to receive chemotherapy after resection should do so. A trial that compared single-agent gemcitabine to observation showed improved survival for patients who received gemcitabine, and a more recent trial comparing single-agent gemcitabine to gemcitabine plus capecitabine showed improved survival for the combination arm. The data for use of adjuvant radiation therapy are controversial.

Patients experience considerable morbidity following resection of pancreatic cancer, with most requiring pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy and those with the most extensive pancreatic resection needing lifelong insulin therapy.

For metastatic disease, the combination regimen of oxaliplatin, irinotecan, 5-FU, and leucovorin (FOLFIRINOX) or the combination of nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine has each shown better antitumor activity and modest survival benefits over single-agent gemcitabine in randomized trials, but the combination regimens have higher toxicity. In second-line therapy, liposome-encapsulated irinotecan added to 5-FU has shown activity. Clinical trials are needed to define second-line therapy for metastatic pancreatic cancer.

Gastroesophageal Cancer

Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical manifestations of esophageal and gastric cancer are discussed in MKSAP 18 Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

Upper gastrointestinal tract cancers are a major cause of cancer deaths worldwide, particularly in Asia and Africa. The incidence has been increasing significantly in the United States and Western countries, albeit with changing pathology. With the dramatic rise in the incidence of adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and proximal stomach, gastroesophageal cancer is now considered a single entity.

Smoking and alcohol use remain the major risk factors for the traditional squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Risk factors for adenocarcinoma also include smoking along with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and obesity. The development of Barrett esophagus as a result of GERD, especially with dysplastic features, is a further risk for developing adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, and regular surveillance is indicated. See MKSAP 18 Gastroenterology and Hepatology for more detailed information on Barrett esophagus and GERD.

Pain or difficulty on swallowing, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, or persistent dyspepsia may be presenting symptoms. Upper endoscopy and biopsy establishes the diagnosis. Endoscopic ultrasonography is routinely used to assess the depth of tumor penetration and presence of involved lymph nodes. In contrast to the evaluation of other gastrointestinal tumors, PET-CT is widely used as part of standard preoperative staging.

Surgery is the primary treatment of locoregional disease, found in approximately one third of patients. Data have shown a survival benefit for preoperative therapy with either neoadjuvant chemotherapy or the combination of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. For those patients with cancer who undergo surgery first and whose cancer is more advanced than stage I, adjuvant chemotherapy is warranted. A recently reported trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with or without adjuvant radiation therapy showed no difference in outcome, raising questions as to the utility of radiation in this setting. Unfortunately, recurrence rates following surgical resection remain high, even with the use of adjuvant therapy.

Treatment of recurrent or metastatic disease is only modestly effective and is not curative.

Approximately 25% of gastroesophageal cancers overexpress the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and it is now standard practice to evaluate gastroesophageal tumors for HER2 overexpression. For these patients only, the addition of the anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody trastuzumab to chemotherapy provides a modest but statistically significant survival benefit. More recently, the anti-VEGF receptor monoclonal antibody ramucirumab has shown modest activity as a non–first-line treatment, either alone or in combination with a taxane.

Gastric Lymphoma

The stomach may be the primary site for extranodal lymphoma, a heterogeneous group of B-cell and T-cell neoplasms, generally treated with combination chemotherapy. A specific variant, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, are indolent tumors that often present with localized disease and concomitant Helicobacter pylori infection. In that setting, standard treatment to eradicate the H. pylori infection results in sustained complete remission in the majority of patients without the need for additional chemotherapy or radiation therapy. MALT is discussed further in Lymphoid Malignancies.

Neuroendocrine Tumors

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) (formerly called carcinoid tumors) arise from the endocrine cells of the digestive tract. Pancreatic NETs arise from the islets of Langerhans cells and were previously called islet cell tumors. Although histologically similar, gastrointestinal and pancreatic NETs behave differently, with several drugs showing activity against pancreatic NETs but not gastrointestinal NETs. The clinical features of pancreatic NETs are discussed in MKSAP 18 Gastroenterology & Hepatology. NETs are rare in incidence but are typically indolent, and patients frequently survive many years, resulting in a high prevalence relative to the incidence.

Well-differentiated NETs exhibit indolent growth. These range from low grade (low proliferative index) to intermediate grade (somewhat higher proliferative index). As would be expected, intermediate-grade tumors are generally, but not always, more aggressive than low-grade tumors. Poorly differentiated, high-grade NETs are highly aggressive tumors that are treated with etoposide plus cisplatin regimens used for small cell lung cancer.

Most NETs do not produce hormones and are termed “nonfunctional,” but approximately 25% do produce a hormone, in which case the hormone-related symptoms are often both the source of presentation and morbidity. Gastrointestinal NETs can produce serotonin, which can cause the classic carcinoid syndrome of diarrhea and facial flushing.

Nonfunctional NETs are often discovered incidentally. The liver is the most common site of metastases, and metastatic disease may be present asymptomatically for years before it is identified.

Given the indolent nature of NETs, observation and serial imaging are appropriate initially; asymptomatic patients may do well, with minimal growth and no symptoms for years, even with metastatic disease. Follow-up examination and imaging at approximately 3 months is appropriate. In patients whose disease appears stable at the 3-month CT scan, further monitoring with serial imaging at 3-month to 6-month intervals is appropriate.

In tumors with somatostatin receptors, the somatostatin analogs octreotide or lanreotide may be used for hormonal control or for stabilization of progressing disease. Hepatic arterial embolization, radiofrequency ablation, or surgical debulking are sometimes used to decrease hormone production or to relieve symptoms of tumor bulk.

When treatment is needed, pancreatic NETs can be treated with temozolamide plus capecitabine, or sunitinib (an anti-VEGF tyrosine kinase inhibitor), or everolimus (a mammalian target of rapamycin [mTOR] inhibitor). Everolimus has more modest activity in gastrointestinal NETs, but the other agents used for pancreatic NETs are inactive in gastrointestinal NETs.

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), derived from the precursors of the interstitial cells of Cajal, are sarcomas characterized by an activating mutation in the c-kit proto-oncogene, which leads to constitutive activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase. Histologically, GISTs are identified by overexpression of the KIT gene, the immunohistochemical marker for KIT protein. Although these tumors may be asymptomatic or discovered during an endoscopic or imaging procedure done for another purpose, most are associated with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms, and some may cause overt bleeding, pain, or signs of obstruction. They are most commonly located in the stomach, which confers a better prognosis, and in the proximal intestine. Other prognostic factors include tumor size and mitotic rate.

For patients undergoing a potentially curative resection of a localized GIST, low-risk tumors do not benefit from further treatment. Higher-risk tumors are treated with adjuvant tyrosine kinase inhibitor imatinib; 3 years of imatinib yields outcomes superior to 1 year of treatment. Imatinib is also used to treat patients who present with unresectable or metastatic disease.